TL;DR

This research contains content that continues from previous research articles, so it is recommended to check the previous research and then return to read this for accurate context understanding.

In this part, we provide detailed explanations of XSLeak vulnerabilities that occur through Timing Attacks among XSLeak vulnerabilities, and XSLeak vulnerabilities that occur in Chrome’s experimental features, and also describe how these vulnerabilities are actually applied and presented as CTF challenges.

Timing Attack belongs to the famous techniques among XSLeak vulnerabilities. When loading pages in browsers, various information can be inferred and leaked using intentional/unintentional time differences.

This process requires precise time measurement, and we introduce a method of measuring using the performance API instead of the conventional method of measuring using the famous built-in JavaScript library Date.

The most famous method of generating explicit time differences is to use ReDoS vulnerabilities to explicitly delay page loading for a long time and use this to leak information desired by attackers.

In addition to such Timing Attacks, another XSLeak vulnerability vector to examine is Chrome’s experimental features. Generally, experimental features, as can be understood from the name, are features that have not undergone as much testing compared to other common features.

The fact that not much testing has been conducted ultimately means there is a high probability that potential security vulnerabilities exist. In this research, there are issues where XSLeaks can occur in Chrome’s experimental features Portal and STTF.

These XSLeak vulnerabilities, unlike other vulnerabilities, have the characteristic that the occurrence vector is not explicit and therefore difficult to discover. For this reason, many CTFs or Wargames sometimes use XSLeak vulnerabilities to make challenges difficult.

We examine how XSLeak vulnerabilities occurring in Timing Attack and Experiments can be used in CTF challenges from the perspective of problem setters.

Timing Attacks

Time measurement via performance API

XSLeak-based Timing Attacks can be broadly classified into two types. There are intentional time differences in the network and unintentional time differences that occur due to browser environment or various external environmental factors, and attackers record the processing time from request ↔ response of such response packets in the network to derive statistics.

Using this, attackers can attempt indirect information leakage of Cross-Origin or identify history records.

To successfully perform information leakage using Timing Attack Based XSLeak, microsecond-level precise time measurement techniques are required. The most famous method for recording processing time for network requests would probably be measuring using the JavaScript built-in library Date.

1 | const startTime = Date.now(); |

If the error tolerance range for time measurement is not very large, the above snippet alone can show sufficiently good results. However, the Date.now() method is not very accurate in precision due to millisecond resolution limitations.

To successfully perform XSLeak attacks, precise time measurement in milliseconds, and further in microseconds, is required. For this reason, recently time measurement is conducted using the performance API.

1 | let start = performance.now(); |

Using the above method, it measures and returns the time taken to request resources from example.org and receive a response very accurately in microsecond units. This is much more precise and accurate than the method of measuring using the existing Date library, and can be used immediately like the Date library without separate installation process as a basic API.

To conduct time measurement in Same-Window, you can proceed as above, and if you need to conduct time measurement in Cross-Window, you can conduct time measurement using the performance API as follows.

1 | let win = window.open("https://example.org"); |

If you measure the time it takes to load only a specific URL by opening a new window alone, more precise time measurement is possible without interference from the external environment. The method of measuring time by separating only a specific window alone enables more precise time measurement than Same-Window, but when browsers load pages, it is rare for only the page to be loaded to be loaded alone.

When browsers load pages, they reflect extension programs individually installed by users in the browser, individually changed browser settings, etc. Due to this, even if you open a new window alone to load a page, if it’s not in incognito mode, accurate time measurement is difficult due to external environments.

To conduct pure page load time measurement without being affected by external environments at all, measurement should be conducted in a sandbox environment.

1 | let iframe = document.createElement("iframe"); |

The most famous method for configuring a sandbox environment is using iframe. As above, using iframe to activate the sandbox attribute and then measure the load time of the example.org page.

This configures an environment that blocks many external additional features including JavaScript execution and external extension loading, enabling pure time measurement of individual pages in the network.

Using a sandbox environment has the advantage of enabling very precise pure time measurement, but the page must allow iframe tag insertion, and if headers like X-Frame-Options are set, it is difficult to conduct time measurement using the above method.

How does precise timing technology play a role in information leaks?

Some people might wonder how conducting such precise time measurement actually plays a role in information leakage. I had the following question when I first read the Timing Attack section on xsleaks.dev: “Can precise time measurement really contribute to actual information leakage?”

The answer to this question was “While critical information leakage might be difficult, indirect information leakage can be possible.”

Here, the standard of “indirect” is defined including information that can be used for fingerprinting purposes, not information that can directly cause substantial damage to operators.

For example, if you send the same request twice to a specific page and measure each response time, and the second request’s response time is shorter than the first request’s response time, you can find out that the page is performing caching processing.

Also, when servers process requests from clients, if there are many operations or logic to process, the processing time increases, which ultimately makes the time difference between request ↔ response longer.

Attackers use this characteristic to include malicious high-performance computation payloads in request parameters. If intentional time delay occurs due to high-performance computation when the server processes such requests, meaningful information can be leaked using this.

Example of Timing Attack using intentional time delay

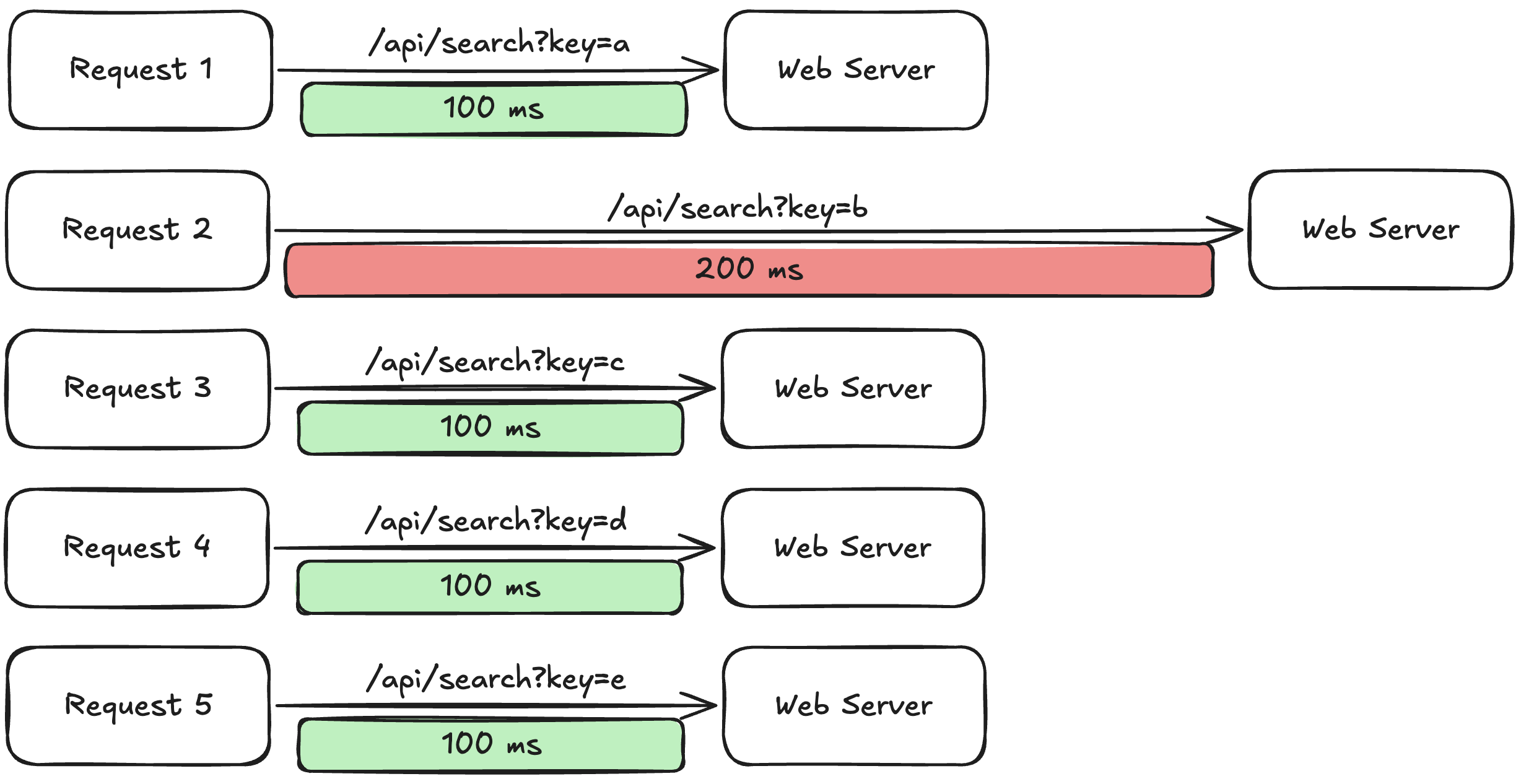

There is also a method where attackers intentionally send payloads that require high-performance computation, but as above, if a longer time than the average response time is measured when requesting the server with specific keywords, it can be inferred that there is logic that conducts additional computation internally when specific keywords are input.

When intentional time delay occurs, the time difference can be directly confirmable time (1-2s or more) or time that cannot be directly confirmed (100ms ~ 500ms difference). For this reason, Timing Attacks require precise time measurement, and to perform this, precise time measurement is conducted using the above methods.

The next section describes what fingerprinting information can be collected using precise time measurement.

Detect cache usage via Timing Attack

The most representative information that can be obtained using time measurement is being able to find out whether a page is performing caching work, which has been continuously mentioned. If a specific page’s response is cached, it becomes a clue that the user has previously visited that page, and this can be used to infer the user’s approximate visit history.

In this process, questions like “You can easily check cache presence by checking page response headers, so why is this evaluated as dangerous?” may be raised. Actually, in Same-Origin requests, you can easily check cache presence by checking Cache-Control headers in responses. However, in Cross-Origin environments, such header information cannot be accessed, so other methods were needed to determine cache presence.

For this reason, techniques to determine whether a page is cached through Timing Attacks emerged, and using this, the following information can be inferred:

- Browsing history inference: Check whether users visited specific websites (banks, SNS, etc.) from attacker sites

- User profiling: Infer interests, political inclinations, shopping patterns, etc. from cached resources

- Personal information leakage: Estimate specific service usage or login status

1 | const bankSites = [ |

This belongs to important security issues that can lead to actual privacy violations. As a method to detect whether a specific page is cached through Timing Attack, if read permissions for Cross-Origin are not blocked, cache presence can be determined as follows.

1 | async function ifCached(url) { |

As above, by checking response data’s encodedBodySize, transferSize, decodedBodySize, etc., you can determine whether the response from a specific page is a cached response. Also, by measuring the time from network request to response and comparing it, you can judge whether it’s a cached response.

However, to check whether a specific response is a cached response, there’s a prerequisite that read permissions for Cross-Origin must not be blocked. If these permissions are blocked, cache presence cannot be checked for Cross-Origin pages.

Also, these cache detection techniques are trending toward having their effectiveness greatly limited due to security enhancements in modern browsers. Due to constraints from CORS and Timing-Allow-Origin headers, for Cross-Origin pages where Timing-Allow-Origin headers are not set, measurement information provided by the performance API can be greatly limited.

In this case, values for duration, redirectStart, redirectEnd, fetchStart, domainLookupStart, domainLookupEnd, connectStart, connectEnd, secureConnectionStart, requestStart, responseStart are all masked to 0, greatly reducing attack effectiveness.

Additionally, in terms of interaction with Same-Site cookie policies, when using the credentials: "include" option, Same-Site cookie policies can directly affect cache behavior.

In Strict or Lax policies, Third-Party transmission is restricted, which can change cache key generation methods, and due to this, even the same page can be classified as different caches depending on cookie policies. Cache presence detection becomes difficult in such cases as well.

As such, cache detection has become much more difficult with the emergence of modern browser defense techniques. Due to this, new Timing Attack methods to detect cached responses are beginning to emerge.

The most representative modern technique is high-precision Timing Attack using AbortController. It forcibly interrupts requests after a very short time (typically 3-9ms), utilizing the difference where cached responses arrive within this time but network requests are interrupted. This enables more accurate cache detection than the duration measurement used in existing performance APIs.

1 | async function detectCache(url, timeout = 9) { |

Besides this, various modern attack techniques exist to check whether responses are cached, but attack techniques not utilizing Timing Attacks are excluded as they are outside the scope of this research topic.

Since caches are generally features created to efficiently conduct loading of pages with large resources, time differences occurring in this part belong to unintentional time differences by attackers. This is because it’s not that attackers explicitly adjusted response times, but it’s intended functionally.

Timing attack via ReDoS

There are also methods to perform Timing Attacks using intentional time differences by attackers rather than unintentional time differences. A representative method is to perform Timing Attacks by using ReDoS vulnerabilities to intentionally cause time delays and then use this to leak information desired by attackers.

ReDoS vulnerabilities belong to one of the well-known vulnerabilities. This is a problem that occurs when security syntax verification is inadequate in regular expression syntax, and this can be used to cause DoS on servers. When DoS occurs, server load occurs, causing time delays in the request ↔ response process.

It typically occurs in processes that handle regular expression matching such as search functions on pages or email pattern matching due to development mistakes (inadequate security processing).

1 | const emailRegex = /^([a-zA-Z0-9_\-\.]+)@([a-zA-Z0-9_\-\.]+)\.([a-zA-Z]{2,5})$/; |

In the above regular expression, backtracking occurs during the verification process, causing processing time complexity to increase exponentially or more. And attackers can exploit this to intentionally cause time delays.

1 | const maliciousEmail = |

The above payload set low repetition counts for a simple example, but in reality, higher repetition counts can be used to exponentially increase time for regular expression processing.

If attackers use intentional time delays and time measurement techniques together like this, it can lead to critical information leakage in specific situations. For example, if a search function allows wildcard character searches and there’s a regular expression vulnerable to ReDoS in the process of extracting such wildcard characters, attackers can inject malicious search payloads like "a" + "*".repeat(100000) and send requests together.

When servers receive such requests, if search results matching a exist, response time greatly increases, and if search results don’t exist, response time is measured as short.

Example of actual information leakage process using ReDoS

As above, by using BruteForcing attacks to send malicious requests, recording time measurements until responses, and then combining only packets with large processing times from request ↔ response, meaningful information leakage can be achieved.

For example, if such vulnerabilities occur on bulletin board sites’ post search pages, this could be used to leak secret post content or secret post titles. Or if it occurs in chat site conversation history search functions, chat history with other users could be leaked.

ReDoS vulnerabilities are one of the representative examples of causing intentional time delays by attackers, and besides this, other vulnerabilities causing time delays (SQLI heavy query, Logical bug, Race condition, etc.) can be used to induce intentional time delays.

In the case of unintentional time differences occurring functionally, attackers usually cannot directly control how much time to delay, but in the case of intentional time differences by attackers, there’s a probability that attackers can directly control time delays, so even simple measurement using general Date libraries instead of precise time measurement has a high probability of confirming differences.

However, since attackers cannot always control response times in all cases, it’s important to clearly confirm the maximum control range of how much time delay can be controlled and decide which measurement method to use.

Connection pool based XSLeak

So far, we have introduced methods to infer/leak various fingerprint information and information that can directly damage operators using precise time measurement and forced time delays using vulnerabilities like ReDoS.

Timing Attacks using precise time measurement can provide more information to attackers than expected. Therefore, many browsers are defending by limiting information obtainable from precise time measurement or allowing developers to separately specify security headers for restrictions.

Many bypass techniques are emerging and developing in response to this, but among them, we’ll explain a method that conducts time measurement in a unique way this time. If there were methods to measure time through performance API or Date libraries before, there’s a method to conduct time measurement by abusing the browser’s socket pool (Connection Pool).

Modern browsers implement something called Connection Pool for HTTP/1.1 connection management, which is an optimization mechanism to minimize TCP socket creation and release costs.

Browsers limit simultaneous connections to the same host, mostly allowing only 6-8 simultaneous connections. For non-same host connections, they generally allow up to around 256 socket connections, and if all 256 sockets are in use for communication, the Socket Pool becomes saturated.

Attackers can exploit this point to perform Timing Attacks that abuse Socket Pool. First, attackers create a state where they occupy all 255 sockets.

1 | // Client |

1 | # Server |

Using the above method to intentionally occupy all 255 sockets in the network keeps 255 socket connections in hanging state. Then the Socket Pool becomes a state where all sockets are occupied except for one remaining socket. Attackers send requests to pages they want to measure time for with the last remaining 256th socket.

Then all 256 sockets are in occupied state, making the Socket Pool saturated. After this, attackers send a 257th request to any other host. Since the Socket Pool is saturated, the 257th request cannot connect immediately and enters a waiting state.

The point when the waiting state for the 257th request is released and actual connection begins matches the point when the 256th socket is released. This is because the remaining 255 sockets are still in hanging state. Unless the processing time for the page the attacker wants to measure exceeds 100000 seconds, the 256th socket is always released fastest.

Therefore, if you obtain the time when the waiting state for the 257th request is released and actual request processing begins, you can conduct time measurement for the 256th request (target page).

1 | performance.clearResourceTimings(); |

Attackers can register the 257th request with the above logic and ultimately conduct time measurement for the desired page. This may have lower precision than conducting time measurement using the performance API. However, this method can also measure time in Cross-Origin, so if the performance API is restricted or precise time measurement is difficult, it’s a method worth trying.

The method of conducting time measurement by abusing Socket Pool uses intended functions to conduct precise time measurement, making defense very difficult or impossible. For this reason, if precise time measurement is needed in Cross-Origin, it’s one of the most reliable methods despite high preliminary complexity.

Besides the method of conducting time measurement by abusing Socket Pool, there’s also a method to check whether connection to a specific page is completely new connection or reused connection using Connection Pool. This information can also be utilized as fingerprint information.

As mentioned above, HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 have various optimization mechanisms for connection management. Among them, connection reuse-related optimization exists, which is a mechanism to reuse used connections once more to improve efficiency when using sockets for specific page connection/visit. Especially from HTTP/2, Connection Coalescing function is provided. This allows different hosts accessing the same web server to reuse one connection.

Using such reuse mechanisms, reused connections respond faster than existing new connections. Using this characteristic, you can detect whether requests to specific pages were connected through socket connection reuse or through new socket connections.

1 | await new Promise((r) => setTimeout(r, 10000)); |

The above method conducts precise time measurement using the performance API and can check whether it’s a connection through socket reuse by using differences in response times of the same page.

In such connection reuse detection techniques, additionally exploiting HTTP/2’s Connection Coalescing mechanism can infer associations between Cross-Origin domains. The Connection Coalescing mechanism mentioned earlier allows all domains included in the TLS certificate’s SAN (Subject Alternative Name) field to reuse the same connection.

Attackers can use this to detect whether domains that users have never visited are hosted on the same server as domains they have already visited.

1 | async function detectConnectionCoalescing(primaryDomain, targetDomains) { |

Through the above method, attackers can infer information about subdomains that users haven’t directly visited, and also, for websites using CDN services or cloud hosting services, attackers can infer facts that seemingly unrelated domains actually share the same infrastructure.

As such, mechanisms introduced for efficiency purposes in HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 can lead to vulnerabilities like XSLeak. Besides the methods introduced in this research, many Timing Attack attacks exist. If you have more interest in XSLeak techniques through Timing Attacks, it would be good to refer to various references introduced in the Timing Attack section of xsleaks.dev.

How does Timing Attacks XSLeak apply to CTF?

Timing Attack attacks are counted among the famous attack techniques among XSLeak vulnerabilities. Also, just the fact that precise time measurement is possible allows attackers to infer and leak quite a lot of information from users’ browsers.

In the case of Timing Attacks among XSLeak vulnerabilities, problems occurring within functions provided by browsers themselves account for quite a large portion. Therefore, there are many cases where problem setters in many CTFs or Wargames apply such techniques to challenges to make challenges difficult.

Actually, in many CTFs, when Timing Attacks are used in challenges, you can frequently see the number of solvers drop sharply. This section will cover how techniques related to Timing Attacks can be applied to challenges from the perspective of problem setters.

This section contains quite a lot of the author’s subjective opinions, and it should be noted once again that the analysis covered in this section is not used for all CTF challenge creation.

Challenge difficulty increase techniques using ReDoS vulnerabilities

ReDoS belongs to one of the vulnerabilities that many problem setters like and use frequently. This vulnerability manifests based on errors in regular expression syntax writing, and attackers can use this to cause intentional time delays.

When intentional time delays occur, attackers can confirm that the time difference between request ↔ response clearly increases, and blind-type information leakage can be conducted using this. Since we covered how information leakage can be conducted using ReDoS vulnerabilities in the above section, detailed information leakage processes are omitted.

In the CTF creation process, when exploit code is executed to obtain the target FLAG in challenges, vulnerabilities should clearly occur and it’s good to minimize probabilistic elements as much as possible. (However, it cannot be asserted that there are completely no probabilistic elements in CTF challenges.)

Therefore, in the case of the author personally, I think about creating explicit challenges rather than speculative challenges as much as possible. In this case, ReDoS vulnerabilities are quite useful. When manifested, attackers can explicitly control time delay intervals, and in this process, time delays are clearly visible to attackers.

When creating ReDoS vulnerabilities as challenges, to increase difficulty further, I think it’s important to hide them so they don’t appear as vulnerabilities. Implement functions as naturally as possible to make discovery as difficult as possible from solvers’ perspectives.

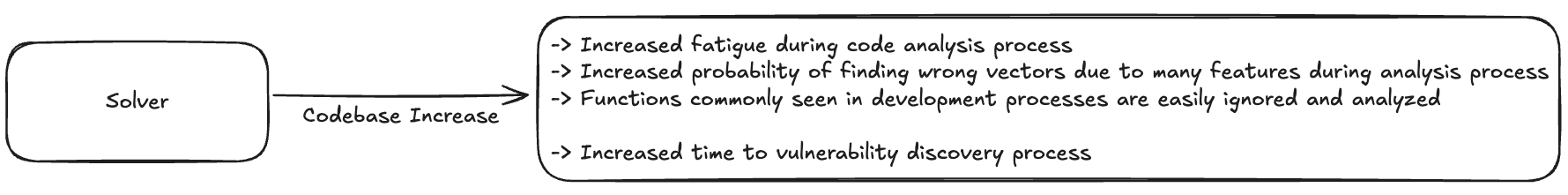

For example, implement intentionally vulnerable regular expression syntax in parts where regular expression syntax is commonly used in development processes, such as regular expressions used for email verification or regular expressions used for password rule verification. And if the code base (LOC) amount is implemented very large, it becomes relatively difficult for solvers to find vulnerable regular expressions.

Predicted thoughts solvers feel as LOC amount increases

Simply thinking, if the code base increases, fatigue increases and the probability of identifying wrong vulnerability vectors increases. This is a method commonly used in creation processes to hide vulnerabilities that seem simple.

Also, when increasing the code base like this, trap functions (commonly called Rabbit Holes) can be added in the middle to make the analysis process more complex. Rabbit Hole means adding vulnerabilities not needed in challenge solving processes or making specific functions or features appear superficially vulnerable.

1 | def sql_injection_rabbit_hole(self, username, password): |

Using blacklist-based filtering and vulnerable-looking SQL syntax to intentionally design it to appear SQL Injection is possible. However, SQL Injection in the above function is not an intended part and vulnerabilities don’t occur. By using appropriate Rabbit Holes like this to configure code bases and designing vulnerable functions to be disguised as natural code, challenge difficulty can be increased.

Problem setters can configure ReDoS discovery-difficult challenge environments like this and create challenges that leak specific information (admin access key leak, blind match flag, intentional time delay for xss) by combining such designed ReDoS vulnerabilities with time measurement-based information leakage described in the above section.

Intentional time delay combining ReDoS vulnerabilities and Connection Pool

Problem setters can also configure relatively high-difficulty challenges by combining characteristics of Timing Attack techniques. When ReDoS vulnerabilities occur, solvers can control request ↔ response time delays as desired. Also, Connection Pool basically allows only up to 256 socket connections, and when over 256 connections occur, next connection requests must wait until remaining sockets are released.

Problem setters can use this characteristic combination to configure challenges. Earlier, we explained that ReDoS vulnerabilities can be made difficult to identify by making code bases large or configuring Rabbit Holes. This can increase challenge difficulty, but there’s a method to dramatically increase challenge difficulty more than the above method.

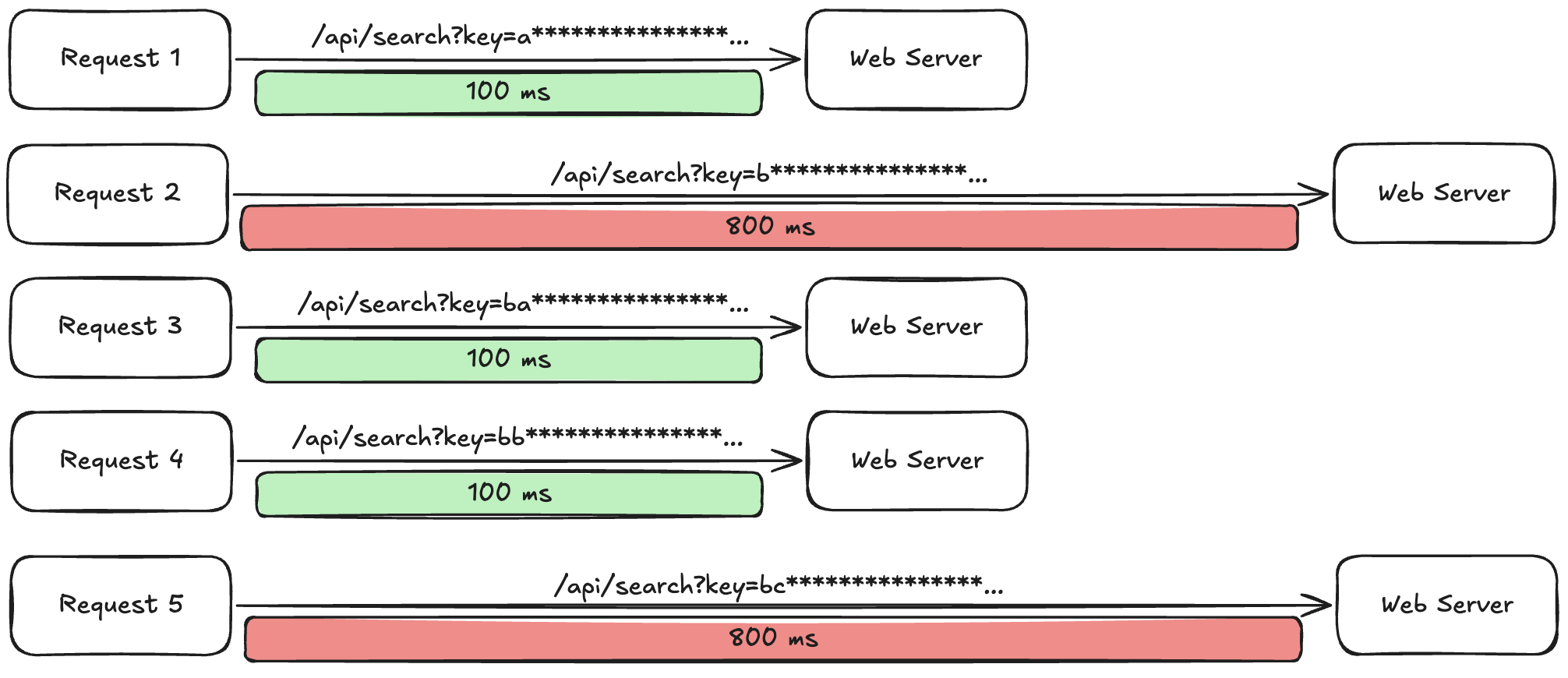

Using this method requires more research and time investment for problem setters to create challenges, but I’m confident it can make ReDoS vulnerability discovery even more difficult. This is hiding parts where ReDoS vulnerabilities occur in libraries rather than providing them in code bases developed by problem setters. (Commonly also called library gadgets.)

This involves finding regular expression syntax vulnerable to ReDoS in libraries themselves and applying them to code bases. (This could be a kind of 0-day.) Since ReDoS gadgets existing in famous and frequently used libraries are rare, ReDoS gadgets are often discovered in libraries with not-so-large usage. By using this to hide ReDoS gadgets occurring inside libraries in challenges, challenge difficulty increases dramatically. Solvers must conduct more code base analysis, library operation method understanding, and in severe cases, even direct debugging.

1 | def sanitize(text_input): |

If ReDoS-occurring gadgets exist in libraries as above, solvers can use this to cause intentional time delays. Here, problem setters can create the first difficulty-increasing part. The second part to increase difficulty is designing ReDoS and Connection Pool abuse linkage.

As explained earlier, Connection Pool basically uses only up to 256 connections, and when all sockets are in hanging state, they wait until existing sockets are released. Then, if you request 256 times connections where intentional time delays occur for long periods using ReDoS vulnerabilities, time delays occur due to ReDoS vulnerabilities and all sockets can be made to be in hanging state.

In this situation, if currently used sockets are not released, requests in the queue continue to be in waiting state. Solvers combine these two to create scripts that maliciously exhaust Connection Pool and inject these scripts into bot functions (assuming functions already implemented in challenges by problem setters).

When malicious scripts are executed, Connection Pool is exhausted in bot environments, making it impossible to send new requests for more than a certain time, and at this time, if bots cannot access specific pages for more than a certain time, they can be designed to return FLAG so solvers can solve challenges.

This is a challenge designed by combining ReDoS vulnerabilities from libraries and characteristics of Timing Attack techniques, and if implemented more complexly, it can be made into challenges with high difficulty. Problem setters design challenges requiring higher creativity and problem-solving abilities based on characteristics and principles of each vulnerability or technique like this.

Also, by looking at challenges from solvers’ perspectives and predicting how solvers might behave in challenges, Rabbit Holes are implemented in the middle to confuse solvers.

Vulnerability chain configuration using blackbox environments

Most challenges in CTFs are usually presented in whitebox format, but some challenges are also presented in blackbox environments. This can be configured as challenges that can test pentesting abilities from web penetration testing perspectives, and actually in web fields, blackbox challenges are presented at about an 8:2 ratio.

When configuring challenges in blackbox environments, information obtainable by solvers is very limited, and attacks must be conducted by collecting as many clues as possible from provided web pages.

Recent web challenges rarely present challenges with only single vulnerabilities. High-difficulty challenges mainly present challenges solved by configuring multiple vulnerabilities in chaining format. Multiple vulnerabilities are chained like SQL Injection → XSLeak → XSS to design exploits.

Cases where challenges can be solved with only XSLeak vulnerabilities are rare, and they are mostly used in middle processes of chaining. For example, assume there’s a challenge in a blackbox environment where caching is not set with headers like Cache-Control but caching is conducted with Redis etc. inside servers, and XSS vulnerabilities must be generated based on cache in Cross-Origin to obtain FLAG.

Also, assume additionally that Timing-Allow-Origin headers are set, restricting access to some properties of performance API.

Since solvers are currently in blackbox environment challenges, they will try various payloads to obtain clues. Since servers conduct caching internally, it’s impossible to check whether caching is currently being conducted internally. However, solvers can infer from seeing Timing-Allow-Origin headers set that there are Timing Attack-based clues in challenges.

Solvers can make requests to check whether servers are conducting caching using AbortController etc. that can bypass most of this since Timing-Allow-Origin headers are set. (This content can be checked in the Detect cache usage via Timing Attack section.)

1 | async function detectCache(url, timeout = 9) { |

Through this, solvers can identify that servers are conducting caching internally, and thoughts can connect to thinking about methods where XSS vulnerabilities can occur using this.

Blackbox-based challenges can become highly speculative challenges if poorly designed. Therefore, it’s always good to add clues so solvers can sufficiently infer and find them. Problem setters can configure Timing Attacks as above to obtain additional clues as middle processes in vulnerability chains, or use Timing Attacks like ReDoS vulnerabilities that directly contribute to information leakage to configure vulnerability chains.

Experiments

In the previous section, we described various techniques where XSLeak vulnerabilities occur through Timing Attacks and how these techniques can actually be presented and applied as challenges in CTFs and Wargames.

Besides Timing Attacks, there are quite many techniques where XSLeak vulnerabilities can manifest. In this section, we will cover in detail XSLeak vulnerabilities that can occur in Chrome’s experimental features among various XSLeak attack techniques.

Among Chrome’s experimental features, we will focus on Portal and STTF functions. This article is research that partially cites content from xsleaks.dev, and content about experimental features is also written by adding some subjective thoughts and content to original articles, which we declare in advance.

Portal

This function is no longer supported in Chrome experimental features. It was provided as an experimental feature in Chrome versions 85~86 in the past, but after this function was first provided as an experimental feature, there were changes in web platforms and utilization gradually decreased, so support was officially discontinued. https://issues.chromium.org/issues/40287334

Portal is a function quite similar to existing iframe functions. This provides functionality to render new pages inside, similar to the role of existing iframe tags. The big difference between iframe and portal is that portal additionally provides a method called activate. When this method is called, pages being loaded in child frames (pages being rendered in portal) immediately move to parent frames and load without page refresh/additional rendering of parent frames.

Also, when rendering pages using portal functionality, parent frames cannot directly access child frames’ DOM trees. Additionally, if onclick event listeners are defined to execute certain logic when specific buttons are clicked inside child frames, events are not triggered even if buttons in child frames are clicked from parent frames.

1 | <meta charset=utf-8> |

The existing iframe function led to various problems that could lead to potential security vulnerabilities being raised by many people due to the fact that it could render yet another new page on pages, and actually various challenges using iframe functions were presented in CTFs and Wargames, conveying to many people that iframe function security is important. Due to this, various frame-related protection functions like X-Frame-Option headers were added, and efforts continue with ongoing security updates.

However, since portal was released as an experimental function for experiments in Chrome, its security is considerably more vulnerable compared to existing iframes. Although functions and roles provided were quite similar to iframe, since security measures were not in place compared to iframe, it was like opening another door to attackers.

One of the biggest security problems with portal functionality is that portal functionality was not affected at all by X-Frame-Options header values. Even if developers applied restrictions on frame elements using X-Frame-Options headers, no restrictions were applied to portal functionality at all. This was a very big security problem and a very dangerous part that could cause many vulnerabilities.

This belongs to one of many potential security problems inherent in portal functionality, and more portal functions and security vulnerabilities can be confirmed through the research below.

Security analysis of

This section focuses on parts where XSLeak vulnerabilities can occur among various potential security problems that can occur in portal functionality.

The simplest technique that can cause vulnerabilities using portal functionality is the XSLeak performance method using Timing Attack techniques. After child frame pages are rendered in portal, onload events are always emitted. Using this, start time can be measured in parent frames and time until portal emits onload events can be obtained.

1 | function timing(url) { |

This fact alone doesn’t seem to suggest that XSLeak vulnerability occurrence is possible using Timing Attacks. Attackers can obtain information about how much time it takes to render specific pages with portal using the fact that portal functionality emits onload events when pages are rendered and timing them. And using this, various information leakage attempts using Timing Attacks can be made.

Attackers can perform port scanning attacks using onload event emission. This enables port scanning by detecting how many times onload events were emitted when rendering specific pages in portal.

- If

err_connection_refusederrors occur during page rendering processes in Chrome,onloadis emitted 5 times. - If

err_invalid_htpp_responseorerr_empty_responseerrors occur during page rendering processes in Chrome,onloadevents are emitted 4 times.

Based on such information, port scanning can be conducted using whether onload events were triggered several times.

1 | async function scanPort(host, port) { |

Port scanning can be conducted like this using how many times onload events were emitted when rendering pages using portal based on host and port. In this process, if onload events are emitted even numbers of times, you can confirm the page is open, and if emitted odd numbers of times, you can know the page is closed.

Port scanning is quite commonly conducted using automated tools like nmap, but it shows that meaningful information leakage is possible using portal and its functional characteristics.

As mentioned above, portal doesn’t allow interaction from parent frames to child frames. However, exceptionally, focus events are allowed. Attackers can use this characteristic to manifest peculiar XSLeak vulnerabilities.

The core of this attack is exploiting HTML’s fragment identifier processing mechanism. When specifying element id to move to in URL fragment, pages try to move to specific elements and focus.

If values specified in fragment match specific element id on pages, pages try to move directly to those element positions and automatically generate focus events in this process. This is behavior defined in HTML5 spec’s fragment identifier processing algorithm.

1 | <body onblur="alert('phpMyAdmin detected!')"> |

As a method to conduct XSLeak based on this characteristic, onblur events are used. Basically, when the above page is first rendered, focusing is set to parent frames (top-level windows). After this, when rendering pages in portal, it tries to automatically focus on text_create_db elements specified in fragment. If child frames find elements matching elements specified in fragment, focusing moves from parent frames to child frames.

onblur events are events that automatically occur when focusing is released, so they occur in parent frames and scripts are successfully executed. However, this attack had one problem: it needed to be able to use JavaScript syntax as a method to check if focusing was released. Due to this, attackers developed this attack to devise methods to detect if focusing was released without JavaScript syntax. This could be solved using CSS syntax.

1 | .x:not(:focus) + div { |

Using this, whether focusing events were released in parent frames can be checked through screen changes, and this information leakage can tell attackers more than expected.

1 | <portal src="https://bank.com/dashboard#account_balance"></portal> |

This is a simple example, but attackers can infer target sites’ internal states step by step like this. The above example attempts information leakage to check if account_balance elements exist on bank site dashboard pages. If onblur events actually occur, it can be found out that account_balance elements exist on victims’ dashboard pages.

Generally, sites show different screens users can see depending on login status like this. If attackers use this attack technique, they can infer step by step what information exists on target sites using victims’ permissions, and such information actually occupies very important parts in information leakage. Attackers can attempt to extract more information by conducting such information leakage in linked manners.

1 | const targets = [ |

Portal has quite similar functions to iframe but can cause many problems due to inadequate security-related processing. If the above attack is executed with victims’ permissions (state logged into various bank sites or platforms), you can check what elements exist on pages only logged-in users can see, and attackers can infer or leak various information by inferring this.

STTF (Scroll To Text Fragment)

STTF (Scroll To Text Fragment) is also Chrome’s experimental feature like portal. This provides functionality to directly link to enable immediate movement to specific text within pages.

Using #:~:text= syntax to include text and browsers highlight this and bring it to viewport.

1 | https://example.com#:~:text=specific%20phrase |

When accessing pages like this, browsers try to find specific phrase text on pages and automatically scroll and highlight. This performs the same role as functions to search specific text on pages using ctrl+f or cmd+f currently in browsers.

Using STTF, developers don’t need to separately implement functions to search specific text within pages, and this has advantages of improving user experience in browsers. This belongs to one of the functions many users are conveniently using currently. Although it’s a convenient function, there are problems where XSLeak vulnerabilities can manifest in this function. Attackers can exploit this to attempt indirect information leakage.

1 | :target::before { |

Attackers initially inject code like above through CSS Injection, then try to search specific text (admin, administrator, secret_data, etc.) on pages using STTF functionality. If text to search exists on pages, requests to confirm text detection success are sent to attacker servers. Attackers can check what content exists on target pages by checking logs on their servers.

Besides directly conducting XSLeak through CSS injection, XSLeak vulnerabilities can be manifested by linking IntersectionObserver API and STTF. Using this API, you can detect whether scrolling occurred to STTF search target text. Using this, by setting IntersectionObserver API inside frames like iframe and checking scroll occurrence on target pages, XSLeak attacks can be performed by sending to attackers when scrolling occurs. This code is attack code in a method modified by referring to the below.

1 | <p style="margin-bottom: 150vh">spacer</p> |

Like this, STTF is used to attempt specific text searches on pages and whether scrolling occurs due to this is sent to attacker servers. Attackers can check what content exists on pages by checking their server logs. This is an additional detection method besides methods using CSS Injection to detect STTF.

This attack is quite similar to XSLeak vulnerabilities occurring in portal. However, XSLeak using STTF searches direct text rather than searching elements on pages, making leaked information clearer and more direct than XSLeak occurring in portal.

As a simple situational example, assume users are logged into national health system sites and there are pages where users’ past diseases and health problem information and records can be checked on those sites. Attackers lure such users to their malicious pages, and when users access attacker pages, XSLeak vulnerabilities occur and health detailed information can be leaked.

1 | https://health.gov/patient-records#:~:text=diabetes |

Like this, by detecting whether searches occur for each disease name through CSS Injection or IntersectionObserver API, target users’ medical information and disease information can be leaked. Like this, XSLeak vulnerabilities using STTF can leak meaningful information about target sites using users’ permissions.

XSLeak vulnerabilities can be manifested in various ways using STTF functionality and various APIs, and attackers use appropriate methods suitable for their situations to leak information about target sites.

How does the XSLeak experimental feature apply to CTF?

Chrome’s experimental features often don’t have as much security-related processing compared to other general functions. Most functions have undergone security processing and stabilization work over countless hours, but experimental features have relatively less such processing proportions. Therefore, experimental features can only be used after separately allowing them in Chrome browser’s separate settings.

For such reasons, experimental features are sometimes presented as challenges in CTFs or Wargames.

Generally, experimental features rarely appear as challenges in Wargames because it’s uncertain whether such features will definitely be applied as official functions in browsers and they are functions with ongoing updates.

However, CTFs with clear progress times sometimes configure challenges using experimental features, though not frequently. This section describes how XSLeak vulnerabilities occurring in portal and STTF among Chrome’s experimental features can actually be applied to CTF challenge creation.

Restriction bypass and XSLeak using portal

Portal performs similar roles to iframe but is a function with much more inadequate security-related processing than iframe functions. Problem setters can implement challenges using this characteristic.

To activate experimental features, experimental features must be allowed with separate settings. Assume challenge environments where automated bots visit URLs with administrator accounts when solvers report specific URLs. (Administrator bots are implemented with puppeteer v5 and allow experimental features.)

Also, assume additionally that challenge environments allow solvers to conduct HTML Injection, and assume the core goal of challenges is stealing administrator cookies.

Problem setters prohibited direct cookie theft requests from being sent to external webhook URLs through CSP policy settings and Same-Site settings to prevent cookie theft situations, and set X-Frame-Options headers to prevent XSLeak through Frame Counting. Due to this, solvers might think methods to leak administrators’ cookies are blocked.

However, solvers who know portal functionality can be used can relatively easily leak administrators’ cookies using Frame Counting XSLeak.

1 | const portal = document.createElement("portal"); |

Solvers can induce bots to visit URLs where malicious scripts like above are injected and steal administrators’ cookies using Frame Counting XSLeak vulnerabilities. This was a simple situational example, but actual problem setters can increase challenge difficulty by designing processes where malicious scripts are injected in challenges more complexly.

XSLeak using STTF

Since STTF provides functionality to directly search text within pages, more information leakage can be attempted, and for problem setters, it can be used as one of very useful sources for challenge creation. XSLeak challenges using STTF are explained based on actual challenges presented as Level 5B - PALINDROME's Secret in The InfoSecurity Challenge 2022 CTF.

This challenge is a challenge where the core goal is stealing FLAG by performing HRS (HTTP Request Smuggling) vulnerabilities and XSLeak using STTF, with various vulnerabilities linked, but we focus on analyzing parts performing XSLeak using STTF.

1 | .alert.alert-success(role='alert') |

The part where vulnerabilities occur core-wise in this section exists in the username part. In Pug templates, !{username} syntax means unescaped output, so HTML Injection can be performed directly in those fields. Also, solvers can know that external image loading is possible since img-src allows all URLs among CSP policy settings.

1 | Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self'; img-src data: *; object-src 'none'; base-uri 'none'; |

Solvers could create attack syntax that leaks direct FLAG values using these two and STTF functionality. Solvers injected malicious HTML syntax that detects whether text matching work actually occurred on pages when using STTF functionality through Lazy Loading.

1 | <div class="min-vh-100">Min-height 100vh</div> |

This uses Bootstrap’s min-vh-100 class to configure each div to occupy viewport height. Due to this, Lazy Loaded images are positioned outside viewport during initial page rendering.

After successfully injecting HTML Injection and completing settings, solvers send requests searching specific text using STTF functionality. If text exists within pages, browsers perform automatic scrolling to that text.

1 | /verify?token=ADMIN_TOKEN#:~:text=TISC{partial_flag |

If scrolling occurs to text, Lazy Loaded images previously outside viewport enter viewport, causing browsers to try rendering those images. At this time, HTTP requests are sent to solvers’ servers, so scroll occurrence can be detected using this. The reason scroll occurrence can be detected like this is that when HTML Injection actually proceeds, pages are rendered as below and div occupies all vertical space in viewport.

1 | This token belongs to <div class="min-vh-100">...</div><img loading=lazy src="...">. If <div class="min-vh-100">...</div><img loading=lazy src="..."> asks for your token, you can give them this token: TISC{ADMIN_FLAG}. |

When actual text matching occurs through STTF, automatic scrolling occurs to that text position, so requests are sent to attacker servers. (FLAG text is located at the bottom of pages.) Solvers can leak entire FLAG by automating this attack using brute forcing.

1 | for char in charset: |

This content focuses on only one part among three vulnerability chaining methods to solve this challenge. If you want to directly solve challenges or check more detailed content, you can check at the link below.

Level 5B - PALINDROME’s Secret (Author Writeup) | CTFs

Conclusion

XSLeak vulnerabilities are establishing themselves as one of the most cunning yet dangerous attack vectors in modern web security environments. Unlike traditional web vulnerabilities, XSLeak has fundamentally different characteristics in that it exploits browsers’ normal functions and web standards to leak information. This means attackers can use browsers and web platforms’ own design characteristics without needing to find direct security flaws, creating situations where detection and defense are extremely difficult.

Particularly, the most fatal characteristic XSLeak vulnerabilities have is that information leakage is possible even in Cross-Origin environments. The fact that indirect access to other domains’ information is possible by bypassing Same-Origin Policy, a core principle of web security, reveals fundamental limitations of web security models.

Despite modern browser vendors introducing various defense mechanisms like CORS, CSP, Timing-Allow-Origin, Same-Site cookie policies, attackers are continuously developing new bypass techniques. This is because XSLeak is not simple implementation bugs but problems arising from web platforms’ structural characteristics. The reality that all new functions browsers introduce for performance optimization and user experience improvement can become potential XSLeak attack paths clearly shows web security complexity.

Based on this, XSLeak presents new-dimensional challenges. These vulnerabilities, difficult to detect with traditional security review methodologies, can occur despite perfect implementation at code levels. This means security review processes must include new perspectives like browser behavior analysis, timing analysis, and side channel verification. Also, when introducing new web technologies or browser functions, security impact assessments from XSLeak perspectives must precede.

For this reason, techniques to determine whether pages are cached through Timing Attacks emerged, and using this, the following information can be inferred, ultimately meaning this presents challenges requiring higher creativity and problem-solving abilities from both attackers and defenders in the evolving landscape of web security.